Violent crime in London: How safe do the public feel?

London has been gripped by a wave of violence that has seen the Met police launch 56 murder investigations in the capital since New Year’s Day. The killing frenzy led commentators to note that London’s murder rate was worse than New York’s in February and March.

The outbreak has left teenagers dead in the street, families robbed of loved ones and futures cruelly snuffed out. London has always been a violent city, forever plagued by gangs and violent crime. But how has the latest horrific spate of killings affected the capital? Atomik Research quizzed Londoners to gauge the atmosphere on the streets in the wake of recent events.

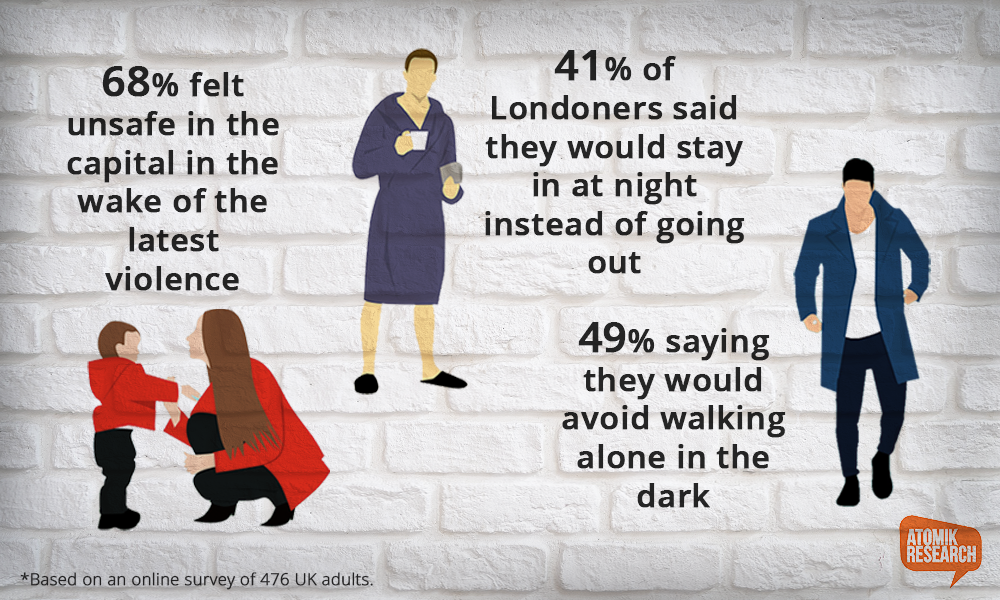

The vast majority – 68% – felt unsafe in the capital in the wake of the latest violence according to the research.

A fifth of Londoners said they would refuse to change their behaviour but many said the violence had affected their habits, with 49% saying they would avoid walking alone in the dark.

Forty-one per cent of Londoners said they would stay in at night instead of going out and 30% said they would avoid visiting certain parts of the capital.

The reason for the tragic rise in murders has been blamed variously on a lack of bobbies on the beat, gang members keeping tallies of stabbings and drill music – a menacing form of hip hop.

Home Secretary Amber Rudd has announced tougher restrictions on buying knives online, extended stop-and-search powers and plans to ban the sale of acid to under-18s.

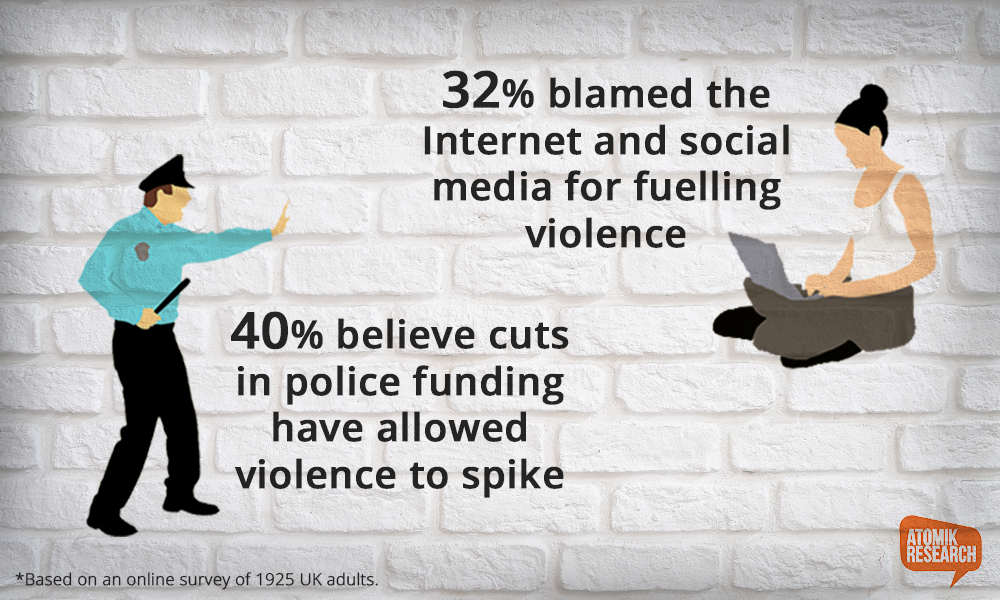

We also questioned nearly 2,000 people across the UK and 65% agreed gang culture was behind the tragic spike in violence. Alcohol and drug use was blamed by 47% while 32% blamed the Internet and social media for fuelling violence.

Ms Rudd has denied that cuts to police numbers were to blame for the murder rate but it was reported at the weekend that leaked Home Office papers showed the reduction in officer numbers ‘may have encouraged’ violent offenders.

Since the Tory-led Coalition came to power in 2010, police numbers have been cut and officer numbers have fallen by 20,000 from 143,734 in March 2010 to 123,142 in March last year.

Our research showed 40% believe cuts in police funding have allowed violence to spike.

Other factors those surveyed attributed to the rise in violence include poverty (34%), unemployment (30%), lack of education (26%), the political climate (19%) and stop-and-search policies (11%).

But the violence has not been confined to London. In Manchester earlier this week a 15-year-old girl was seriously injured and a 14-year-old girl arrested.

Nearly half (48%) of those polled about violence across the country said harsher prison sentences and more neighbourhood policing were potential solutions, according to the research.

Many commentators believe that a rise in stop-and-search increase tensions, leading to more violence but only seven per cent of those surveyed believed decreasing the level of stop-and-search would help the situation.

Forty-three per cent of people believe better education around gangs in schools would help reduce violence. More social support for kids from disadvantaged backgrounds and ploughing money into youth services were seen as potential solutions by 36% of people who responded.

But ultimately more resources for police were seen by many as the best way to tackle the tragedy on the streets. Thirty-five per cent of those questioned said the government should pour more resources into policing, with 26% saying youth services needed more cash.

BY PIERS EADY